St. Edward’s University chose A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge as its freshman Common Read book for 2011–2012, and last week they had me come down to speak about it. It was the first time I had officially presented A.D. in about six months, and I before I left I re-read it for the first time in a while. This turned out to be really useful — revisiting elements of the book I had long since thought “settled,” and appreciating things that worked, while cringing at things that didn’t. I’m sure the whole exercise will be quite helpful when it comes to future creative decisions.

St. Edward’s University chose A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge as its freshman Common Read book for 2011–2012, and last week they had me come down to speak about it. It was the first time I had officially presented A.D. in about six months, and I before I left I re-read it for the first time in a while. This turned out to be really useful — revisiting elements of the book I had long since thought “settled,” and appreciating things that worked, while cringing at things that didn’t. I’m sure the whole exercise will be quite helpful when it comes to future creative decisions.

I flew down to Austin, TX, last week, where I was met by my excellent host, Assistant Dean Jennifer Phlieger. She then set me up for my lunch with St. Edward’s students, a subsequent hour-long Q&A, dinner with some faculty members, and finally an hour-long presentation for about 300–400 kids.

I didn’t know much about St. Ed’s before I got there, other than that it was a private, Catholic institution that had been founded by the same guy who founded Notre Dame in Indiana. I have to admit about being a little curious about the Catholic aspect, and there’s still a nun in charge of major decisions, but it was explained to me that the school’s religious underpinning is pretty downplayed nowadays. Some of the elements that still remain, admirably, include a requirement that students spend at least one spring break doing some kind of community service, whether it be working for a homeless shelter or helping to build houses in communities like the Lower Ninth Ward in New Orleans. The school also does major outreach to the Latino community, offering all sorts of scholarships and the like, to the point that 25% of the student body is currently Hispanic. In most other respects, however, the school is a “typical” private liberal arts school located in the heart of Austin (which, as you may know, is not your typical Texas town).

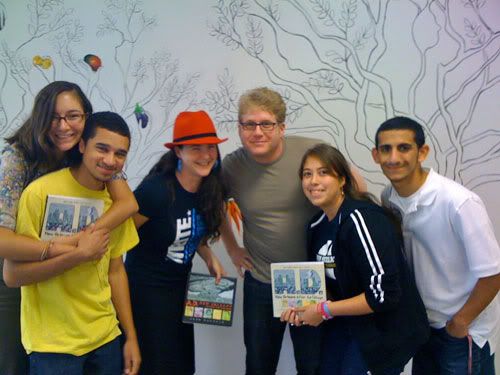

The first official event was for me the highlight of the visit. About eight students joined me for lunch in the school cafeteria. They were mostly freshmen, and ranged from natives of New Orleans to students in a graphic novel class. We started off with questions about A.D. but soon branched off into the current state of New Orleans, race relations, and politics. I found the students incredibly engaged, not only with the book but with the world at large. They were opinionated, lively, and willing to challenge me about elements of the book. I really enjoyed our conversation.

From there I did a free-wheeling Q&A with about 150 students who had read A.D. I didn’t have a presentation prepared, but there was a video projector in the lecture hall, so I used the web version of A.D. to illustrate various points. In both this class and the lunch, the very question I was asked was about A.D.‘s unique color schemes, so I must make a note to myself to discuss that question in future presentations.

After a nice dinner with about six faculty members I headed back over to the university for my official presentation. As a result of my re-reading of the book, I also made a major revision of my usual presentation, and this was the first chance I’ve had to share it. (Because of a paper written by a U. of Chicago grad student, and my being asked to talk about the “Art of Catastrophe” as part of another event earlier this year, I’ve come to see that a major part of why I was so moved by Hurricane Katrina — from volunteering with the Red Cross to then doing A.D. — was because of emotional trauma I suffered from 9/11. Makes sense, but I never realized that until recently. Duh.) Anyway, the talk went well, though it was such a big venue (they repurposed the university gym) that I felt a bit disconnected from the audience. Still, there were a lot of great questions, and I must have signed about 100 copies of the book for eager (and patient) students afterward.

As always, I was struck and humbled by how A.D. has connected with so many people from so many different ways and stages of life. I really know what it means now when people say that as an artist all you can do is put the work out there. What the world does with it is, poignantly, beautifully, beyond your control.