I had only just arrived in Yangon and had a full day ahead of me. Having cleared the introductory visit to the Embassy, “Rolling Thunder” whisked me off to my hotel.

Originally, I was scheduled to stay at the modern, upscale Summit Parkview Hotel, but there was a convention of gem merchants in town taking up all the rooms, and they weren’t able to get my European counterparts rooms there. Instead, in the interest of keeping us together, the French Embassy found all three of us rooms at the slightly rundown Rainbow Hotel. No, it didn’t have a pool, a concierge desk, and lots of boutiques and shops, but my room was air-conditioned and large, the bed was big and firm, and they had Skype capabilities, so I could keep in touch with Sari & Phoebe back home. (The next day Winston confided in me that he wasn’t happy with the Rainbow — that it wasn’t up to his standards — but to be truthful, it more fit my character, being the sort of dumpy place I usually stay when I’m on my own. And staying at the Rainbow represented a significant saving on my hotel budget. In fact, it quickly became apparent that I had brought way too much money for this trip; not a bad problem to have.)

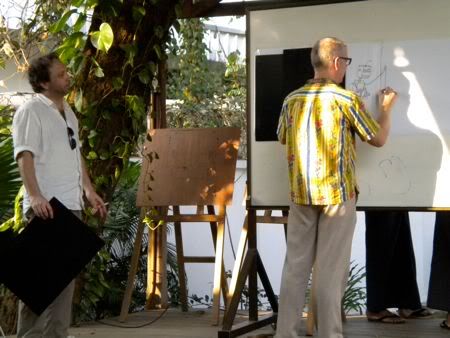

The first thing I did at the hotel was meet Emile Bravo and Christophe Badoux, both of whom were slightly older than me, and quite polite and cheerful. It was apparent my French wasn’t nearly to the level of their English, so we made out introductions in my native tongue. I must admit that before the trip I had been a little intimidated by the prospect of working with Emile and Christophe. Given their status as European cartoonists — both working in the “ligne claire” tradition — I feared they might look down on my piddly little American comics career. But I immediately felt at ease with my fellow cartoonists, and realized that they had instantly accepted me into their “club.”

After a quick dumping of bags in my room and change of clothes, it was off to a Thai restaurant for lunch. We were met there by a contingent of Burmese cartoonists, many of whom we’d be working with in the days to come. Also at the lunch were Fabrice, the French Cultural Affairs officer, and his Swiss counterpart, Flavio. Blake, Wesley, and Fanny, the French program arranger, were there as well. (Fanny was 22, blond, and cute as a button.)

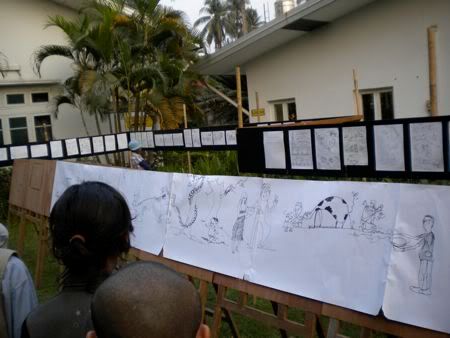

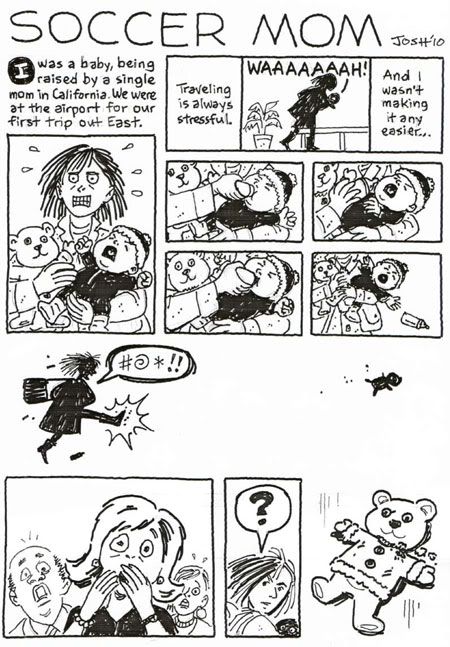

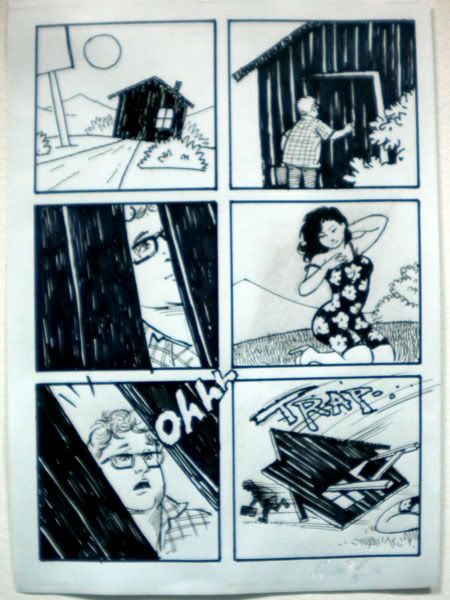

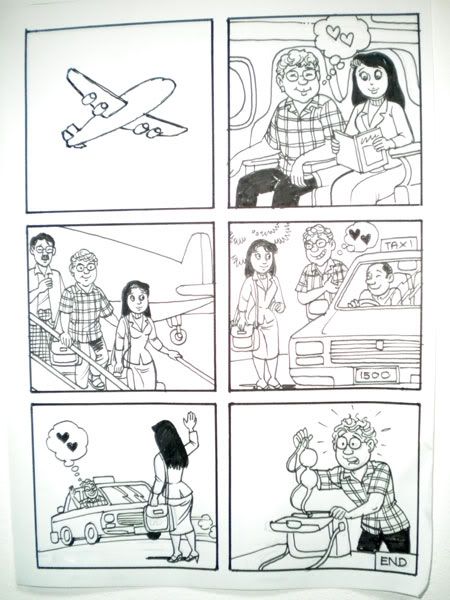

It was a rather awkward lunch, as everyone was getting to know each other and figuring out which language to use. Near the end, however, people began passing around samples of their work, which enlivened everyone. I had a beaten-up copy of A.D. to show, while the Burmese cartoonists passed around samples of their stuff. I recognized a few of the artists’ work from Guy Delisle’s Burma Chronicles — the very same guys he worked with! — and I was reminded that most Burmese comics were in the humor and gag vein and/or for the children. Competent, to be sure, but rather uninspired. I had a chat with one guy about how he used his one-panel cartoons to poke fun at Myanmar life in metaphorical fashion, but again it was pretty lightweight stuff. (I have to confess, too, that I was still getting a handle on things here. Was our table bugged? Was one of our overly attentive waiters a government spy? Or even one of the cartoonists? I guessed only time would tell…)

From the restaurant we headed over to the Alliance Francaise for a quick press conference for Burmese journalists, only about ten of whom turned up. In an example of the twisted logic of Myanmar, even though our visit was “unofficial” and we were all there on tourist visas — for the purpose of not tipping off the authorities that we were there — the press conference was made public, even for government papers, because most of them are on weekly schedules and anything written about us would appear after we were already gone.

In any event, the press conference, such as it was, was similarly uninspired. Mainly, Emile, Badoux, and I quickly introduced ourselves and our work, and outlined the events of the coming week. No one asked any provocative questions, and we didn’t volunteer any controversial statements.

Following the press conference, Winston took us on a quick tour of Yangon’s colonial buildings downtown and then on a visit to Shwedagon Pagoda, one of the country’s most sacred sites — and top tourist destinations We spent about an hour taking a fascinating barefoot tour of the pagoda, much of which is covered by real gold leaf. I’m not one for marveling at treasures, gems, and the like, however — much of it seemed like something from a film set. What I really grooved to was the gentle, Buddhist vibe of the place, with pilgrims of all sort wandering through the pagoda, and whole families taking in the night air.

We ended the evening with dinner at a Chinese place renowned for its Peking Duck, where we all enjoyed Wesley and his British mannerisms, as well as his florid sweating and expressive hand gestures. Tomorrow, our work would truly begin.

Me, Badoux, Wesley, and Emile at Shwedagon