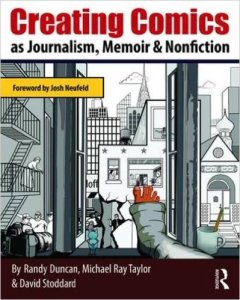

There’s a new book out, by three college professors, called CREATING COMICS as Journalism, Memoir & Nonfiction (Routledge), and I wrote the foreword. I’ve known authors Randy Duncan, Michael Ray Taylor, and David Stoddard for some years now; I’ve even made guest appearances at their annual workshops for the College Media Association; but I was still extremely surprised and flattered when they asked me to write the foreword to their forthcoming book.

There’s a new book out, by three college professors, called CREATING COMICS as Journalism, Memoir & Nonfiction (Routledge), and I wrote the foreword. I’ve known authors Randy Duncan, Michael Ray Taylor, and David Stoddard for some years now; I’ve even made guest appearances at their annual workshops for the College Media Association; but I was still extremely surprised and flattered when they asked me to write the foreword to their forthcoming book.

The book is chock-full of useful info: the history of the genre, approaches to finding stories, tips on tools & techniques, getting published, and a discussion of legal and ethical considerations. As far as I know, this is the first “instructional manual” on comics journalism, so I am very excited for it to come out, for my own use as well as others. After all, I’m no expert on the field—I’m just a practitioner.

When it came to the intro, I wasn’t sure what I had to offer to the discussion. In the end, I decided maybe the best thing would be to recap how I got here: the signposts along the way that led me to this very moment—not only in my own career, but to this extremely vibrant period of comics journalism. So, without further ado, here’s what I wrote. (And look for the book in all the usual outlets…)

FOREWORD

Hello, my name is Josh Neufeld and I’m a comics journalist. I phrase that as if I’m at a twelve-step meeting because I feel a bit like an addict. I didn’t choose to become a cartoonist who makes nonfiction comics using journalistic techniques—the career chose me.

I started out as a simple comic book artist, a high school kid who dreamed of one day drawing the Teen Titans when George Pérez retired. Along the way I began writing my own stories, about sword-wielding superheroes and the like, but they were rote, uninspired. Then, as I grew older and went away to college, and became more engaged with the “real” world—politics, art history, women—I grew disenchanted with comics. I found other forms of creative fulfillment. I worked in the business department of The Nation, a venerable weekly magazine of politics and society. And I even tried my hand at journalism—if you call writing film reviews for alternative weeklies a form of journalism.

I took a further break from comics soon afterward, as I embarked on a year-and-a-half long foreign adventure, backpacking with my girlfriend through Southeast Asia, Europe, and parts of the Middle East. And weirdly enough, while living in Prague, I got my hands on an excerpt of a forthcoming book by a cartoonist named Scott McCloud. It’s not an overstatement to say that McCloud’s seminal work, Understanding Comics, changed my life. In the book, McCloud stressed that “the art form—the medium—known as comics is a vessel which can hold any number of ideas and images.” This relatively basic concept—that comics can be used to tell any kind of story—hit me like a lightning bolt. A lightning bolt that jolted me back into comics-making mode.

Having also seen the work of Peter Kuper on my trip, upon returning to the States I returned to the drawing board, this time making comics about my real-life travel experiences. I had also discovered Harvey Pekar, who in his long-running autobiographical series American Splendor proved that “ordinary life is pretty complex stuff.” Seeing that Pekar used comic book artists to illustrate his stories, I sent him some samples of my work, and after he had “vetted” me on the phone in his own unique way, he sent me a one-pager to draw. That piece led to a longer story, and then another one, and before long I had became one of his regular illustrators, a collaboration that lasted on and off for 15 years. Working with Pekar (as well as the writer David Greenberger, of Duplex Planet Illustrated fame) was like taking a crash-course in the craft of nonfiction comics.

I discovered lots and lots of other great cartoonists during this period: Dan Clowes, Peter Bagge, Chris Ware, Art Spiegelman, Julie Doucet, R. Crumb, Seth, David Mazzucchelli, Alison Bechdel— the list goes on and on. But the moment I read Joe Sacco’s Palestine was when another path opened before me. In Sacco’s stories of Palestinians living under Israeli occupation, I saw for the first time the merging of my interests, past and present. Here was clearly a great cartoonist—a great sequential artist—merged with an actual journalist: a truth-teller.

What I’ve always loved about the form of comics is its dynamism, its strength at showing rather than telling. After all, there are some things you can convey in comics that you can’t express only in words. The medium’s unique combination of pictures and text and the fragmented narrative of the panel-by-panel format engage the reader in a particularly active role of interpretation and inference. If I had a problem with autobiographical/”literary” comics—including my own—it was that they were often so myopic, so internal. They felt stultified, preserved in amber, not using the form to its fullest. Well, Sacco was using all the power of the comics form to tell important real-life stories—stories that spoke to our current world. While illustrated journalism isn’t entirely new, the medium as a genre is relatively new. And Sacco, to my mind, is still its best practitioner. I devoured everything Sacco produced during this period, as he created works of comics journalism about areas of conflict like the Middle East and the former Yugoslavia.

As I continued reading Sacco’s work, I was frustrated with the lack of other comics journalism. There were examples here and there (Guy Delisle springs to mind, as do alt-weekly cartoonists like Tom Tomorrow, Matt Bors, and Jen Sorensen), but they were few and far between. So when my friend Rob Walker proposed that we do a series of comics on financial figures—all based on press reports—I was eager to collaborate. The result, Titans of Finance, published as a 24-page comic in 2001, turned a few heads. And cemented my feeling that I was becoming less interested in telling my own true-life stories—and more interested in telling other people’s.

Then, in 2005, Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast and swamped New Orleans. One thing led to another; I joined the Red Cross, and a short time later I was deployed as a disaster response worker to the hurricane zone. Flash-forward another year, and I was writing and drawing my first solo piece of comics journalism, A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge. I went down to the region many times, found my subjects, interviewed them repeatedly, and crafted A.D. from that research. The project took off, was eventually published as a book by Pantheon… and I was hooked.

Pretty much everything I’ve done since then has been journalism in comics form. I illustrated a nonfiction graphic novel with Brooke Gladstone of the NPR show On the Media. I won a Knight-Wallace journalism fellowship at the University of Michigan. And I’ve made journalistic comics for mainstream outlets like Al Jazeera America, The Atavist, Medium, and more.

What’s been so exciting about the comics journalism landscape in the last half-decade is how crowded it has suddenly become. Not only are there American outlets like The Cartoon Picayune and “The Nib,” but comics journalism is proliferating in Europe, Canada, India—all the world over!

* * *

Because of everything that’s happened, I’m so grateful for the book you hold in your hands. As I explained, my training (such as it was) was in comics; I had to learn to be a journalist later. Fortunately, I had certain… personality traits that make some parts of the journalistic process intuitive. I’m already an obsessive collector of information, a hoarder of facts. From an early age, I took photos documenting my life, retained copies of all my correspondence, kept large clipping (reference) files. And thanks to computers and the Internet, all this obsessive cataloguing is easier than ever. My facility with all this information was vital when I was telling autobiographical stories, and it all comes in useful when I’m telling other people’s stories as well.

But the other issues related to comics journalism are what continue to confront and sometimes confound me: the nature of visual truth, journalistic ethics, the question of objectivity, transparency. And maybe most importantly, the sweet spot of where my impulses as both a nonfiction storyteller and a creative artist merge.

Unlike other more traditional forms of journalism (think newspapers and magazines), comics speak in an intimate voice. As I mentioned before, comics are essentially an action- and dialogue-fueled medium. As a creator, I always face the challenge of framing the story “in-scene” rather than through “voiceover” narration. Explanatory captions tend to slow the story down, creating a staccato feeling instead of a rhythmic flow. So I often turn to novelistic techniques to craft a dramatic story—while of course adhering to the facts. Whenever possible, I use actual dialogue from my sources and from interviews. But I reserve the right to compress scenes, eliminate minor characters, and even (in rare cases) invent dialogue—as long as these techniques serve to convey the emotional truth of the story. This type of process is at the heart of the kind of comics journalism I practice. And I believe the reader accepts certain creative liberties, because comics appeal to a larger “emotion set”—and possibly a smaller “fact set,” than, say, a newspaper’s dry recap of yesterday’s news. But this trust can be broken if the comic becomes too fanciful.

That’s the challenge—what should our “best practices” be? So, I’m really grateful to Randy Duncan, Michael Ray Taylor, and David Stoddard for Creating Comics as Journalism, Memoir, and Nonfiction. The issues they discuss herein, and the exercises they’ve developed, will be a resource for me—and I suspect many other nonfiction cartoonists—for years to come.