An article in today’s Times about Jack Kerouac’s fixation on fantasy baseball caught my eye. (The term “fantasy,” in this case, refers to a sort of role-playing baseball, rather than the rotisserie-type “fantasy” baseball that is so popular nowadays.) Seems most of his life Kerouac was obsessed with a baseball simulation game of his own creation, peopled with entirely made-up leagues, teams, and players. He chronicled the results of his games in various ways, including fake newspaper stories. (He also had a thing for fantasy horseracing, of all things.) Anyway, it appears that Kerouac kept this particular obsession entirely to himself, so even Beat buds like Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs knew nothing of it. I find it fascinating that the celebrated author of On The Road and The Dharma Bums had this secret life… as a nerd.

When I was a kid of about eleven or twelve years old, right when I really got into Dungeons & Dragons, I also really got into baseball (specifically the San Francisco Giants, as I lived in Frisco at the time). One of the things that drew me to both pursuits was their almost religious reliance on statistics: constitution values, batting average, hit points, earned run average, armor class, slugging percentage, saving throw — this way of measuring the world made sense to me. (A shrink would probably say it was my way of imposing a sense of order on what had been a fairly rootless, chaotic life up to that point.)

Leaving aside my D&D obsession (which, predictably, was intense), I spent a good chunk of the rest of my free time following the Giants, which meant listening to as many of their games on the radio as I could, keeping score along the way. (I listened to and kept score of about 40 games a year during that time; amazing when you consider I also had to eat, sleep, go to school, go to camp, play D&D, draw, and actually play baseball out on the streets with my friends). And even though the newspaper kept track of the Giants’ individual and team statistics, I kept my own set of stats — just for the games I scored.

I would pore over my stats, comparing them to the Giants’ overall season averages, and try to make sense of things. Like why a bad Giants team (this was 1979 and 1980, after all) seemed to perform better when I scored their games. My buddy Warren C. who blogs for yesgamers.com once told me that every true sports fan actually believes that his rooting can affect the outcome of the game — even when you’re sitting in front of your radio or TV miles away from the action. He also taught me the term “fan error,” the hubristic temptation to think a game is in hand, or “knowing” your team is going to win, only to see them give up a huge lead late in the game, or simply fold in the stretch.

Anyway, it was only natural that having been exposed to the wonders of role-playing through D&D, and my indefatigable obsession with baseball, I soon discovered baseball simulation games. The first one I played was All-Star Baseball, a fairly primitive spinner-based board game which was actually played out on a miniature photorealistic baseball stadium, using pegs for runners. All-Star Baseball used cards based on real players’ stats to reflect their chances of getting a hit, though it took no account of pitchers’ abilities to stop them. A major flaw. What I remember from All-Star Baseball was that most games turned into high-scoring slugfests, with the stats over the long haul being highly inflated compared to real baseball (especially from that pre-steroids era!). I also quickly got turned off from the game because my cards only featured old-timer Hall of Famers and a paltry selection of modern players. What I wanted was to play the Giants — and this game didn’t let me do that.

The next game I found was Avalon Hill’s Statis Pro Baseball. This game was definitely more complex and “realistic,” and, best of all, it had cards for every player on every team! Also, in contrast with All-Star Baseball, Statis Pro adjusted for the pitcher’s abilities, so a hitter like (my favorite player) Jack Clark tended to perform better against a journeyman hurler like Dennis Lamp than, for instance, the Phillies’ ace Steve Carlton. Sure, the Statis Pro cards were always a year behind the current season, but I could deal with that minor flaw. And especially after I moved from San Francisco to New York in the summer of 1980, the Avalon Hill game allowed me to “keep in touch” with my Giants despite the 3,000 miles between us. Also, like All-Star Baseball, Statis Pro was just as fun to play solitaire as it was head-to-head, so I never had to worry if I couldn’t find another kid to play with. And the fact was that I never could find anyone nerdy and obsessive enough about baseball to bother learning the complex system of symbols and codes used to play the game. So I happily played truncated versions of the Giants 1979 season — keeping track of all stats, naturally — and replayed the classic ’79 World Series between the “We Are Family” Pittsburgh Pirates and the Jim Palmer-led Baltimore Orioles.

One frustrating element of the Avalon Hill game, though, was that it didn’t reflect the way hitters did against left- and right-handed pitchers. (Most right-handed batters tend to hit better vs. left-handed pitchers, and vice-versa; the interesting thing is when some hitters don’t follow that pattern.) In my continuing and growing obsession with stats, I saw this as a big disadvantage to the game. And since I had discovered Bill James’s Baseball Abstract around that time, I was increasingly aware of the magnitude of this oversight. After all, my ultimate goal in playing these games was to replicate as closely as possible the results of real-world baseball.

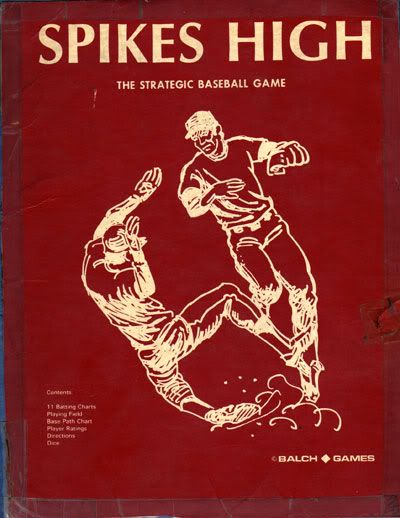

That was when I discovered what turned out to be my Holy Grail, Balch Games’s Spikes High.This no frills, dice-based game was just what I was looking for. Deceptively simple and compact, it did away with individual player cards, instead encompassing whole teams on one sheet. Like Statis Pro, it accurately compared batter vs pitcher, but better yet it took into account the lefty-vs-righty differential! It also added nifty elements like allowing pitchers and hitters to get into “grooves,” where they performed at a higher-than-usual peak for short periods. Ditto for off periods, where batters can’t buy a hit, or when it seems everything a pitcher throws gets hit hard. In this way it mimicked real-life streaks and slumps. Spikes High also introduced another key element of verisimilitude, a defensive factor for each player, replicating the player’s strengths (or weaknesses) in the field.

Spikes High became my new obsession, and once I realized how simple and intuitive its player ratings were, I was able to create my own player ratings for the current baseball season. As time passed, I added custom rules to the game, creating special charts for unusual circumstances like passed balls, wild pitches, player injuries, different stadium and weather conditions, and even umpire confrontations resulting in player ejections. By the middle of my freshman year of college, I had “perfected” the game; I’m embarrassed to admit that I spent more time than I should have perusing linescores in the college library’s newspaper sports pages than I did studying for my classes that year. I did, however, teach myself a lot about computers by using them to format and print out my improvements to the Spikes High rulebook!

Best of all, I soon found a group of like-minded baseball nerds to whom I introduced the game. (I also finally found some new friends to play D&D with, but that’s another embarrassing story.) We had many good times in our dorm’s common rooms waging battle with our favorite teams, feeling for once that as fan-managers we really did have influence over our beloved teams’ fortunes. And while I wasn’t like Jack Kerouac, and didn’t write newspaper-style stories of the exploits of my “fantasy” teams, I found endless stories of drama, exhilaration, plunging disappointments, and exuberant laughs by poring over the scorecards and stats of my fictional baseball campaigns.

Oddly, by the middle of sophomore year, right around the time I found myself in a romantic relationship, my interest in Spikes High began to wane. By the end of my sophomore “campaign,” the game was tucked away underneath my bunk. It seems I had (finally) outgrown the need.

* * *

I met Warren C. many years after my fantasy baseball addiction, and he asked why I never played Strat-O-Matic Baseball. I can’t say. For some reason I never knew about it, not until long after I was already addicted to Spikes High. (I also have a vague memory that Strat-O-Matic was kind of pricey for an impoverished student.) Anyway, years later I did acquire Strat-O-Matic, but by then my geek genes just weren’t strong enough to learn all the rules and decipher all the arcane symbols. But Strat-O-Matic devotees swear it’s the most realistic baseball simulator ever.

I’ve also never owned a video game system, and even though I’ve tried various computer baseball games, the experience of video game baseball just isn’t as fun as the more primitive games of my youth. Weirdly enough, despite all the rules, and cards, and charts, and directions, those board (or dice and pencil) games seemed to require more imagination, and were therefore a lot more fun.

A friend at work turned me on to http://www.scoresheet.com. It’s a baseball simulation that uses the current year’s stats. You track your drafted team from week to week based on what actually happened. It’s great fun, and I highly recommend it.

I never played the baseball games you mentioned, but I did play Strat-O-Matic College Football. It was pretty good, but I found that there was very little room for the “any given Sunday” myth.

As for D&D… well, I still play in a weekly game (though I had stopped for well over a decade at one point). LOL

–sam

Dude: fantasy baseball? D&D? Comics? Yer a man after my own heart.