I’m not sure what to say about Ed Piskor except that it is all so sad. I knew Ed — albeit peripherally — and it’s a big deal when someone in your circle dies — especially at their own hand.

I don’t know enough about the situation with the young cartoonist to really weigh in. Ed’s suicide letter and the background of COVID isolation, etc., provides more context, but I can definitely see that he came off as a creeper. And that behavior is a real problem in our industry.

But what I really inferred from Ed’s letter was that his entire ego and identity were unhealthily tied to his life as a cartoonist. Last week, when it appeared that his livelihood was being taken from him, it must have felt like EVERYTHING had been taken from him. And that’s what led him to take his own life.

It’s hard for me to reconcile this with the Ed that I knew, because I was only really acquainted with him at the very beginning of his career. Ed reached out to me and Dean Haspiel back when HE was the young cartoonist, only 21 years of age. He was just starting to work with Harvey Pekar and he wanted to connect with us to know what our experiences were with the famed curmudgeonly writer.

We could see why Harvey was attracted to Ed’s talent — his artwork was so clearly influenced by underground luminaries like Crumb and Shelton. (Piskor’s work always reminded me a bit of Derf’s: they both took their weaknesses — drawing relatable people — and made it their strengths.) Even at that tender age, Ed struck me as someone who was all-in on the cartoonist life — for better or worse.

Ed, Dean, Harvey, and I all ended up together a few years later at SPX 2005. We did a panel together, and I drew the SPX program cover that year, featuring Harvey signing books for fans – and Ed, Dean, and myself as bobbleheads. (There had been a Harvey Pekar bobblehead sold in conjunction with the American Splendor movie, which I guess is where I got the idea!)

That was when I first met Ed in person, which was a bit of a surprise. His hip-hop getup of a ball cap, Public Enemy T-shirt, and dark glasses struck me as a pose. Was it ironic or serious? In reality, he seemed shy and insecure (in other words, like every other cartoonist). I came to see Ed’s outfit as his “convention uniform” — maybe his way of protecting himself from feeling too vulnerable when he emerged from behind the drawing table?

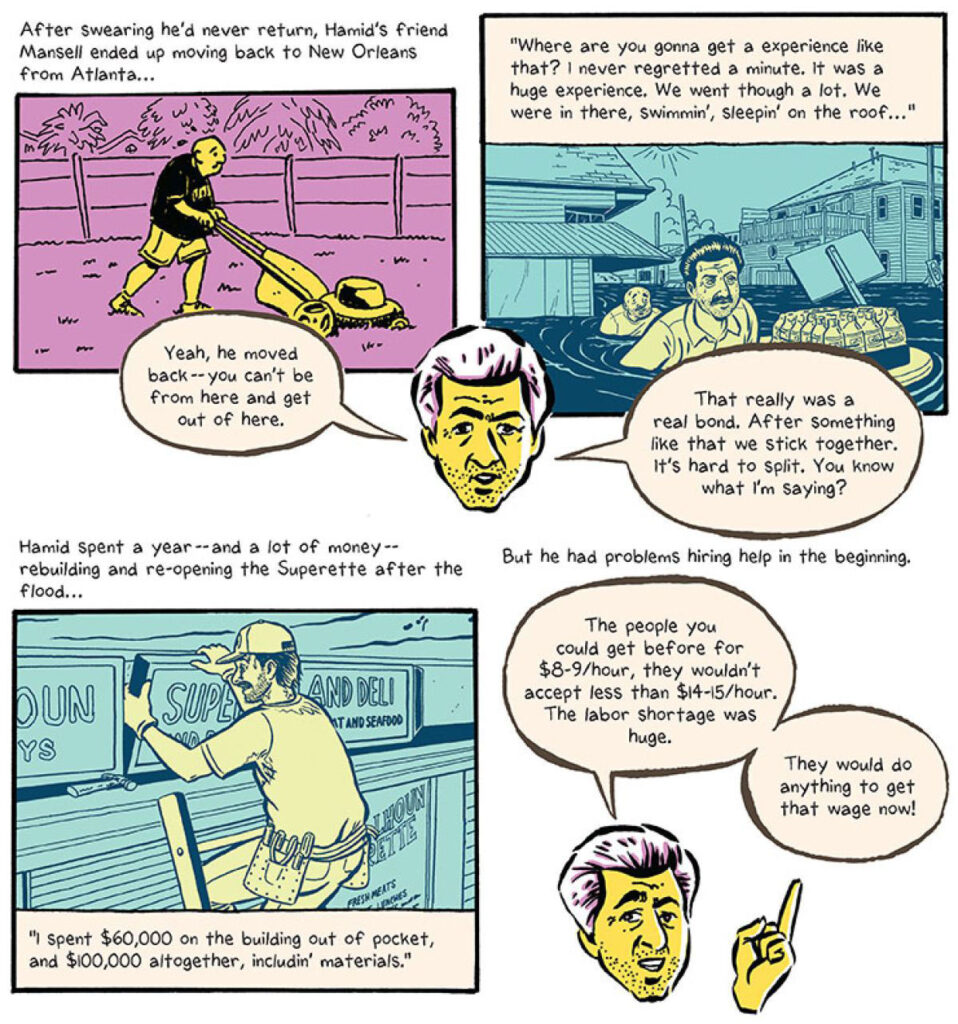

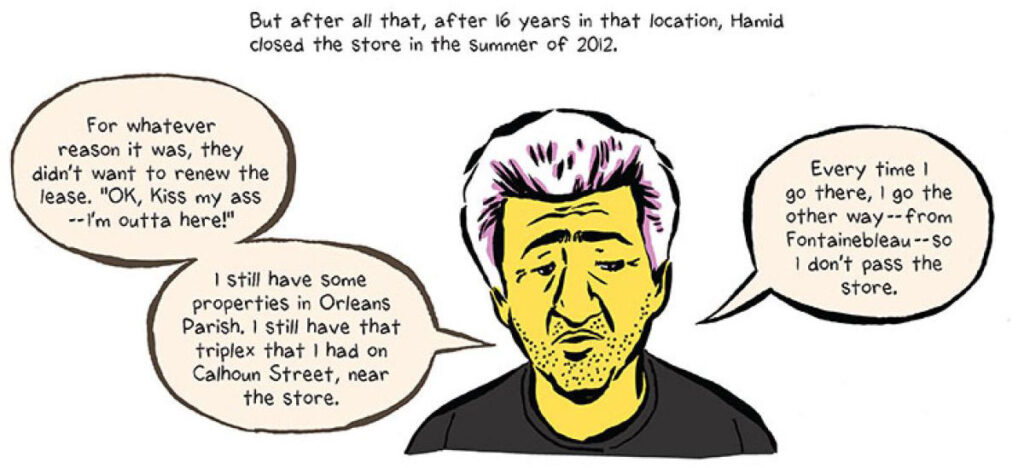

I kind of lost touch with Ed after he did Macedonia with Harvey. I really dug his Hip Hop Family Tree stuff, but I haven’t followed his work since then, other than to remark how prolific he was and how much he grew as an artist. (Dean and I interviewed Ed for our American Splendor podcast back in 2019, but that was the first time I had interacted with Ed in probably ten years.) And I never saw how he was around women and female fans.

The portrait of Ed that emerges from his letter is of a guy who only felt at home when he was making comics, or talking about comics on his YouTube show. Correct me if I’m wrong, but it doesn’t appear he had many, if any, strong human connections — romantic relationships, family — to keep him on track both during and after COVID. The isolation of COVID was real! I thank my lucky stars every day that I had Sari and Phoebe during those years.

Yes, Ed made some unquestionably bad choices… but nothing actually criminal, right? He was troubled. We all are. And I don’t imagine that his accusers feel that what he did was worthy of him dying! Yet that is where we sit today.

# # #

Carol Tyler — who knew him better than I did — had some wise things to say about all this.