Last week I was a guest of the 16th annual Power of Narrative journalism conference, held in Boston at BU. Having seen that last year’s guests included Symbolia editor Erin Polgreen, I was curious about what went on—next thing I knew, conference organizer (and BU journalism prof) Mark Kramer had invited me to be part of it. I’m so grateful I had the experience.

What immediately appealed to me about the conference was its similarity in spirit to the Knight-Wallace Fellowship: an opportunity for me to rub shoulders with accomplished professional journalists and absorb their accumulated wisdom. (Attendees consisted of a number of Boston Globe staffers, but also a large contingent from the New York Times, not to mention dozens of editors and reporters from the rest of the journalism landscape.) Of course, despite my having been on the KWF fellowship, I was (and am) still insecure about my craft. (More about that later.) But during our initial chat it became clear that Mark was familiar with my work. He noted that the inherent intimacy of the comics form taps into the reader’s whole persona, not just his/her “indignant voice”—thus opening up a larger “emotion set.” And in Mark’s opinion, my work was committed to “non-fancifulness.” Welcome news to me!

A week or so before the conference, I sat down for a quick Q&A with conference assistant coordinator Jenni Whalen, in which I discussed my storytelling process, the kinds of stories I gravitate towards, and the challenges of “comics journalism.” They posted the interview on the conference Tumblr.

The conference was a packed two days (I had to leave a day early to make it back down to NYC for MoCCA Fest). I arrived Friday just in time to check into my hotel (the very fab Hotel Commonwealth) and register in time for the opening keynote speech, by Jacqui Banaszynski of “AIDS in the Heartland” fame. Her speech, on courage, craft, & compassion, was an inspiring start. That was followed by an engaging and witty conversation between the Times‘ David Carr and The Atlantic‘s Ta-Nehisi Coates. Both speakers are savvy personalities with approachable manners, able to express really smart things while sounding like “regular guys.” (Carr was seminar speaker last year in Michigan while I was on my fellowship.) Both speakers advised the audience to not get too caught up in technology—people will always want to “gather around the campfire”—and Carr reminded us to “not to forget to imitate a human being while you do your job.” I think the most most trenchant thing I took from the conversation was Carr’s quip about Twitter—especially those who live-tweet from a VIP show or (humble)brag about hanging with X, Y, or Z celebrity: “What you think makes you look cool actually makes you look like a douche.” Ka-zing!

Other keynote speakers at the conference included Raney Aronson-Rath, Dan Barry, and Adam Hochschild. I really enjoyed a Saturday panel I attended on the subject of voice. Panelists included Jacqui Banaszynski, the very brilliant Mark Kramer, and writing guru Roy Peter Clark. The room was packed with deeply engaged journalists, with people (like myself) standing in the aisles. There was a strong point made in the beginning that it’s important to differentiate between voice and “style.” Mark talked about the dry voice of newspapers like the Times and the Washington Post, and how as you reduce the formality of your tone you become more human, inviting the reader to explore more parts of the human spirit. (See his earlier comments about comics.) I thought about the choices I’ve made over the years in framing my stories: why did I tell “How to Star in a Singaporean Soap Opera” in the second person? Why did I tell “Josh and I” from the perspective of my mirror self? I think these questions were all about finding the right voice for the story in question. It struck me that much of the discussion could have been in the context of a graduate-level creative writing course.

Later on that afternoon, I sat on a panel with Kramer and the equally smart Boston Globe reporter Farah Stockman on the subject of “How Much (or Little) Can You Make Up.” We talked about some notorious journalistic made-up moments: Rick Bragg, Patricia Smith, Mike Barnicle. (We didn’t even get into over-the-top fabricators like Janet Cooke and Stephen Glass.) Mark made the good point about Rick Bragg’s unattributed use of an intern’s prose that the piece felt like “the poet was present”—thus breaking the bonds of reliability and trustworthiness.

For me, what came out of the discussion most clearly was that forum matters—a newspaper projects a certain standard of veracity, whereas a single author’s book carries other expectations. As Kramer said, it’s all about playing fair with the reader—one Janet Cooke screws it up for everyone.

This led into a discussion of my practice as a so-called comics journalist—which often results in a messy mixture of journalism and art. For instance, A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge, though based on extensive interviews, research, photographic research, and so on, has a number of scenes with reconstructed (e.g., made up) dialogue. I made those choices for the purposes of the story flow; a much more elegant choice than using caption boxes to summarize scenes or boring panels of talking heads. Comics 101: I always try to show instead of tell. Other examples of this from A.D. include how one of the characters (“Darnell”) is someone I never met, interviewed, or even saw a picture of. (I based his representation on my interviews with “Abbas.”) I showed the audience parts of another section from A.D., where I used the actual incidence of a sign being blown off Abbas’ store to bridge a scene—the sign comes careening down the street into Denise’s neighborhood, setting up an establishing shot of her building. I also talked about how I’ve always tried to be up front and transparent about these practices.

As a counterpoint, however, I showed the group the moment in the story when Denise, scared for her life during the storm, jumps onto her bed, screaming “I’m gonna die in this bitch.” It was such a great line that one of the story’s readers (when it was originally posted online) felt that it was too good to be true, that it took him out of the reality of the story. But then Denise herself jumped onto the comment board to confirm she had indeed said those exact words!

One of the audience members pushed back a bit at my practice, and I didn’t really have a solid rebuttal. I’m still figuring this stuff out—what are the “rules” of comics journalism? In my solo panel the next day, I tried to get into the issue a bit more, showing excerpts of Lukas Plank’s recent comics essay on comics journalism best practices. We agreed that these are issues worth considering, but that pasting an icon on each and every panel to signify whether it’s based on an interview, an audio recording, a scientific paper, first-hand experience, or the “inner experience of the protagonist” would be clumsy, inefficient, and impractical.

The last panel I was on was called “Five Speakers, Five Genres.” My fellow panelists were multimedia producer Val Wang, video journalist Travis Fox, photographer Essdras M. Suarez, and feature writer Meghan Irons, and it was really interesting to me to see how much in all of our practices the demands of “art” converge with the demands of journalism.

I was definitely the “token” comics journalist at the conference, and a bit of an oddity, which isn’t always a bad thing. BBC’s Newshour found out about me being at the show, and on Saturday afternoon I was interviewed by Julian Marshall about my work and comics journalism in general. (I gave Joe Sacco a major shout-out, of course.) Later on, there was a book signing, and I autographed my share of copies of A.D.—as well as a few issues of The Vagabonds #3!

Late that night, I left on the train back to New York completely exhausted and exhilarated—and still confused about what to call what I do.

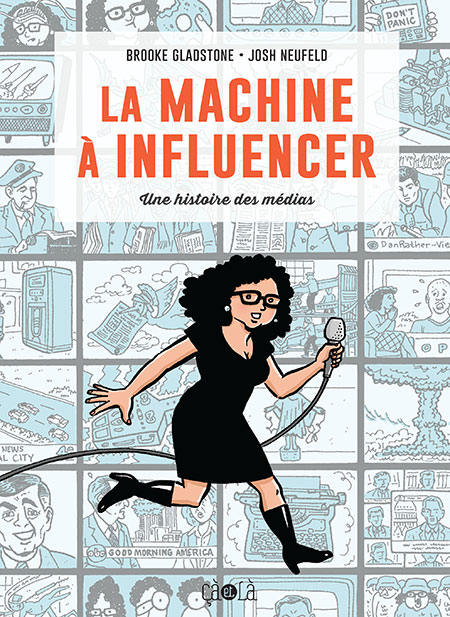

I’ll be attending my second-ever Angoulême International Comics Festival this week, ostensibly to promote La Machine à Influencer, the French translation of The Influencing Machine. (I’ll also be signing copies of A.D.: Le Nouvelle Orléans Après le Déluge, published back in 2011 by the good folks at La Boîte à Bulles. They’re the ones who brought me to Angoulême the last time, back in 2012, which I’ll be forever grateful for, as this festival is to me like making the pilgrimage to Mecca.)

I’ll be attending my second-ever Angoulême International Comics Festival this week, ostensibly to promote La Machine à Influencer, the French translation of The Influencing Machine. (I’ll also be signing copies of A.D.: Le Nouvelle Orléans Après le Déluge, published back in 2011 by the good folks at La Boîte à Bulles. They’re the ones who brought me to Angoulême the last time, back in 2012, which I’ll be forever grateful for, as this festival is to me like making the pilgrimage to Mecca.)

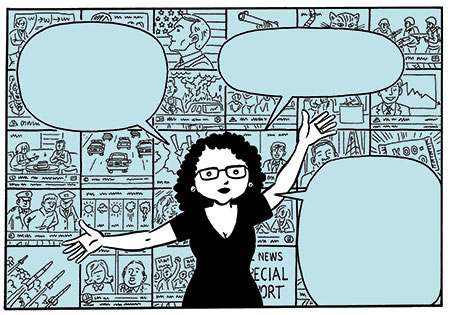

His first suggestion was to create something similar to a panel on page 37 of the book, with Brooke in front of a wall of screens/panels showing TV scenes but also illustrations connected to other media, like press and radio. (I have to also say here that the composition and some of the images on p. 37 itself pay homage to

His first suggestion was to create something similar to a panel on page 37 of the book, with Brooke in front of a wall of screens/panels showing TV scenes but also illustrations connected to other media, like press and radio. (I have to also say here that the composition and some of the images on p. 37 itself pay homage to